On a regular work inspection, a few days before the sprint ends:

- “It doesn’t work.” - The QA team rejects a feature.

- “It works fine; that part wasn’t specified.” - The developer replies.

- “The feature doesn’t work like the user expected.” - The product owner adds

- “But, it meets the acceptance criteria!” - The developer frowns.

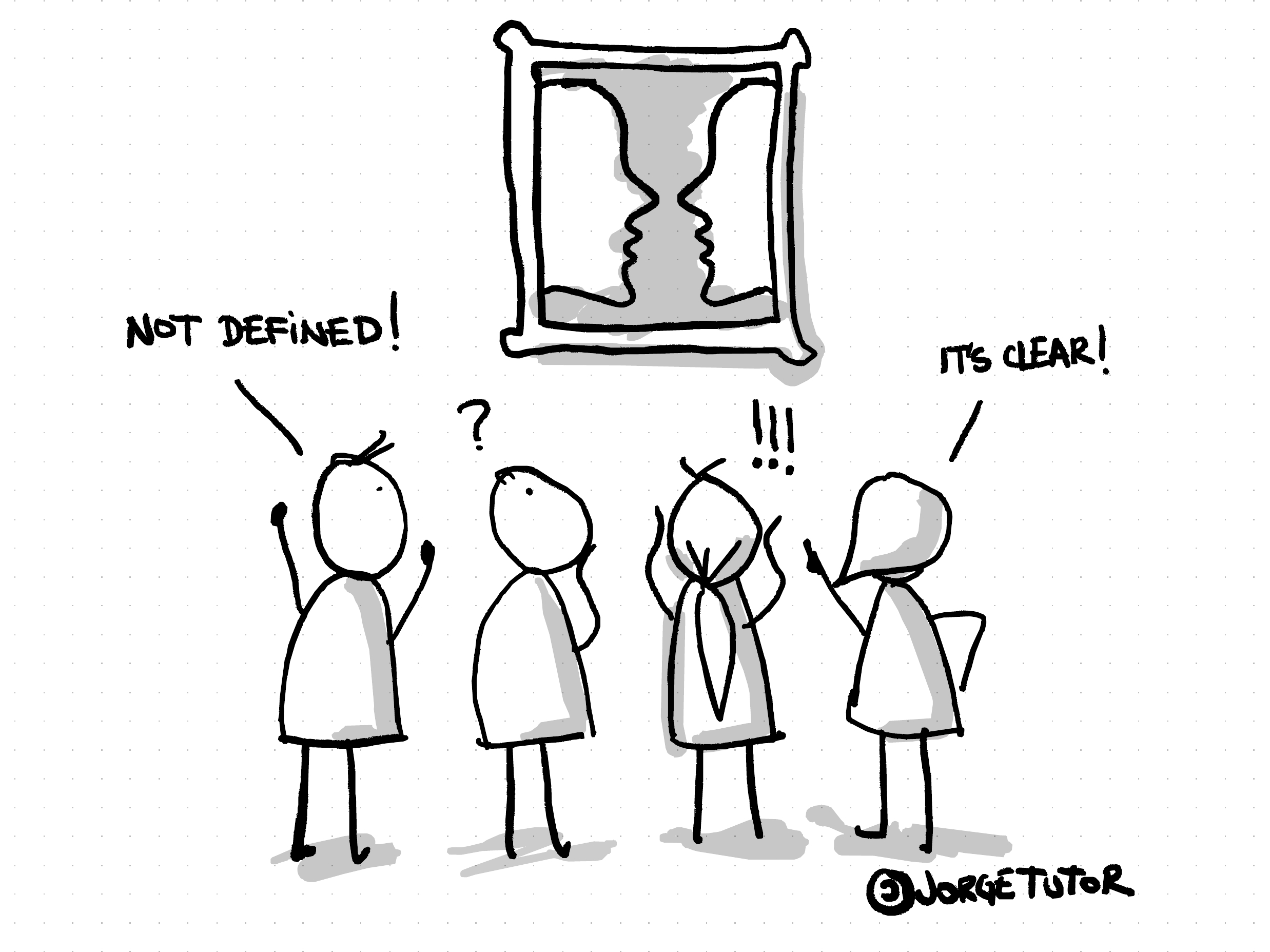

Silence. A debate brews. One side argues it should have been specified, the other insists it was clear enough.

Who is right? The truth is, that everyone interprets ‘clear’ differently.

- If AC are too vague: Teams make assumptions, leading to misunderstandings.

- If AC are too strict: Developers might meet them literally but miss real user needs.

- If teams rely only on AC: They lose accountability for critical thinking and problem-solving.

What is the Acceptance Criteria (AC)?

The Acceptance Criteria (AC) define the conditions a product, feature, or user story must meet to be considered complete. They serve as a contract between business and development teams, ensuring everyone understands what “done” really means.

Why Acceptance Criteria Matter

AC define the conditions that must be met for a feature to be considered complete. They ensure:

- Clarity & Alignment – Everyone understands what success looks like.

- Reduced Risk – Issues are caught early, not after release.

- Objective Evaluation – Features can be tested against concrete conditions.

- Scope Control – Helps prevent last-minute scope creep.

- User-Centric Focus – Ensures we build what users actually need.

Good AC prevents misunderstandings, sets expectations, and keeps projects on track. But if they’re too vague, they lead to confusion. If they’re too rigid, they limit creativity. And when conflicts arise, AC can become a double-edged sword—a tool for clarity or an excuse for failure (“but it wasn’t defined!”).

What Makes AC Good?

Bad AC: “The login system should prevent too many failed attempts.” (How many? What should happen?)

Good AC: “When a user enters an incorrect password 3 times, they should see a message: ‘Your account is locked for 15 minutes.’”

All stakeholders must agree that the AC are:

- User-focused – Aligns with actual needs.

- Aligned - They align with business and technical feasibility.

- Clear – Simple and easy to understand.

- Concise – No unnecessary details.

- Complete - They cover all essential aspects of the feature.

- Flexible - They provide enough detail to avoid misunderstandings, but not so much that they dictate implementation.

- Specific – Defines success in measurable terms.

- Testable – Can be objectively verified.

Who Owns Acceptance Criteria?

It’s a shared responsibility:

- Product Owners draft AC based on business and user needs.

- Development Teams refine them to ensure technical feasibility.

- Scrum Masters facilitate discussions to clarify gaps.

- Business Analysts or Clients may contribute to complex requirements.

Takeaways

- Ambiguity is a shared failure. If it’s unclear, it’s everyone’s responsibility to clarify it early.

- AC define the what, not the how. Teams must have the freedom to implement solutions.

- “Not specified” doesn’t mean “not needed.” Think beyond checkboxes—does the feature truly solve the problem?

Next time someone says, “It wasn’t in the AC,” ask: Was it truly unclear, or was it just convenient?

What’s your experience with AC conflicts? How do you handle them?