Somewhere between validating an issue and rewriting a spec, I had to remind myself: “You’re not the developer anymore.”

As a former software engineer turned IT manager, resisting the urge to jump in and “just do it myself” has been one of the hardest lessons to learn.

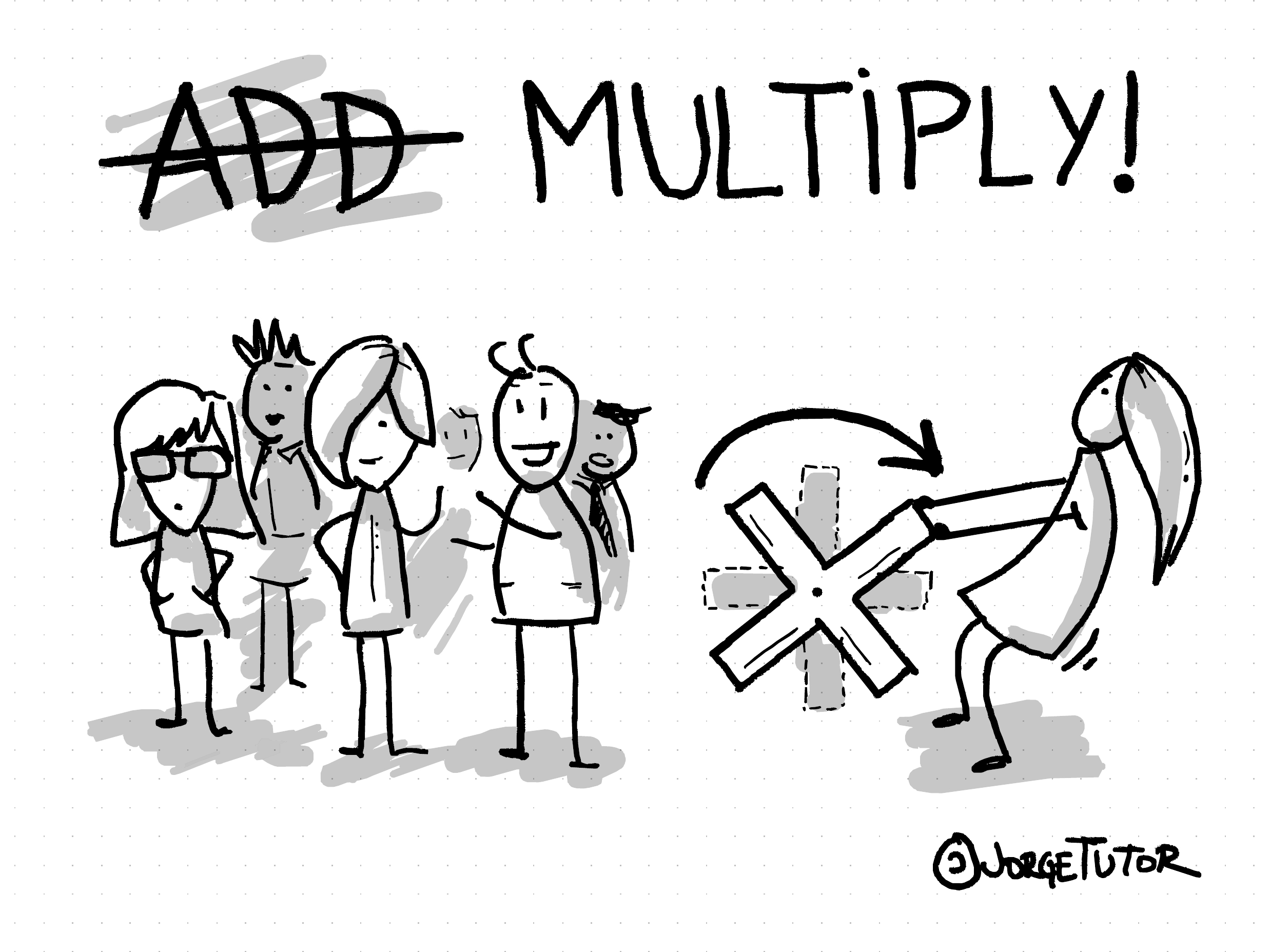

In The Making of a Manager, Julie Zhuo explains that great managers don’t just add value—they multiply it. That means improving purpose, people, and processes instead of doing the work yourself. But here’s the catch: When you’re skilled at something, stepping back feels unnatural.

I’ve come to realize that my “speed” as a manager (developer) is an illusion. It’s not fair to compare my flexibility—changing requirements on the fly—to my team’s structured workflow. And let’s be honest: skipping documentation or planning because I “know what needs to be done” is cheating.

It’s like a football coach jumping onto the field to replace the goalkeeper. If that happens, the problem is much bigger than who’s standing in the net.

The Ego Trap

One of the hardest things to admit as a manager is that your expertise is no longer your most valuable asset, your ability to empower others is. The ego whispers, “You’re still the best at this. You could solve it faster.” But if you’re coding, fixing, or micromanaging, ask yourself:

- Are you helping—or just proving you can still do it?

- Are you adding value—or preventing someone else from growing?

- Are you saving time—or actually slowing the team down?

The Real Job of a Manager

Many organizations reduce management to task assignment, time tracking, and cost control—basically, administrative work. But real leadership is about:

- Shaping Culture – The way your team operates, collaborates, and innovates starts with you.

- Strategic Alignment – Ensuring that what’s being worked on is what truly matters.

- Long-Term Growth – Developing your people, not just managing workloads.

How Do You Know You’re Holding the Team Back?

One way I check myself is by watching for signs of the Karpman Drama Triangle :

- Victim – “Why is everything on me?” → Reality: Have I empowered the team?

- Persecutor – “Why can’t they just do this right?” → Reality: Have I set them up for success?

- Rescuer – “I’ll just fix it myself.” → Reality: Am I solving problems or creating dependency?

A manager’s role isn’t to do—it’s to enable. The best way to measure impact? Look at how well your team performs without you.

If you’re a manager, what helped you shift from adding value to multiplying it?

See also

- The Illusion of Stability: Why Stagnation Is the Calm Before the Storm

- Acceptance Criteria: a tool for clarity or an excuse for failure

- Deadlines Won't Wait: How Timeboxing Keeps You in Control

- Navigating Change: How to Lead Teams Through the Kübler-Ross Change Curve

- Stop Micromanagement Before It Starts